|

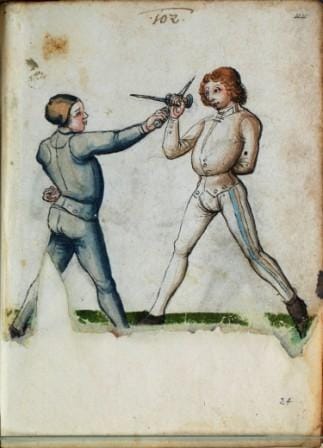

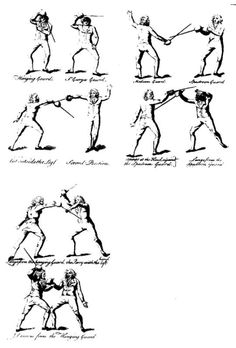

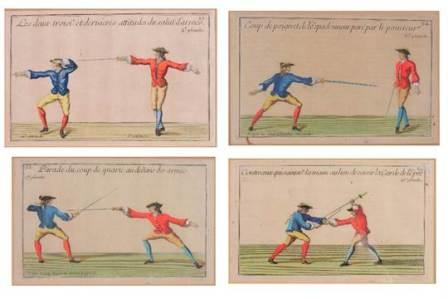

In the 18th century Late Baroque / Rococo period, the French style of fencing with the smallsword and later with the foil (fleuret), in origin a training weapon for smallsword fencing. By the year 1715, the rapier had been largely replaced by the lighter smallsword throughout most of Europe, although treatments of the former continued to be included by authors such as Donald McBane (1728), P. J. F. Girard (1736) and Domenico Angelo (1763). 1763. fencing print from Angelo Domenico's instruction book In the course of the 18th century, the French school became the western European standard to the extent that Angelo, an Italian-born master teaching in England, published his L'Ecole des Armes in French in 1763. It was extremely successful and became a standard fencing manual over the following 50 years, throughout the Napoleonic period. Angelo's text was so influential that it was chosen to be included under the heading of "Éscrime" in the Encyclopédie of Diderot. There are medieval predecessors, such as the Burgundian Le jeu de la hache("The Play of the Axe") of ca. 1400, but the history of the classical French school begins with the foundation of the Académie des Maistres en faits d’armes de l’Académie du Roy (also known as the Ecole Française d’Escrime) by Charles IX of France in December 1567. Charles IX around 1572. One master produced by this school was Henry de Saint Didier a 16th-century fencing master and author of a 1573 treatise, titled Traicté contenant les secrets du premier livre (Treatise containing the secrets of the first book on the single sword), dedicated to Charles IX. Henry de Sainct-Didier The modern foil was developed in France as a training technique in the middle of the 18th century; it provided practice of fast and elegant thrust fencing with a smaller and safer weapon than an actual dueling sword. Fencers blunted (or "foiled") its point by wrapping a foil around the blade or fastening a knob on the point ("blossom", French fleuret). German students took up that practice and developed the Pariser ("Parisian") thrusting small sword in Academic fencing. By the 18th century, the French school had become the western European standard to the extent that Domenico Angelo, an Italian-born master teaching in England, published his L'Ecole des Armes in French in 1763. It was extremely successful and became a standard fencing manual over the following 50 years, throughout the Napoleonic period. Angelo's text was so influential that it was chosen to be included under the heading of "Éscrime" in the Encyclopédie of Diderot. "Pariser" small sword, from which the French foil was derived Foil When we think about noblemen of the Middle Ages in Europe, we immediately picture them dressed up in knee length pants, beautiful bright colored jackets with gold trim, wide-brimmed hats with lush, poofy feathers, and of course an elegant sword decorated with a shiny, intricately monogrammed guard. The sword was an inseparable part of every nobleman’s outfit, being the best indication that he belonged to the nobility. Every nobleman in the 17th Century, whether he was rich or poor, did everything possible to have his own sword – even if he had to sell some of his belongings to buy one. Just having a weapon was not enough though, it was even more important that they know how to handle it masterfully. So what were the options for, say, a future musketeer, to learn the art of fencing in 17th and 18th Century? Actually there were a lot of opportunities: from private lessons with fencing masters to attending a fencing school, and even to learning fencing at the Academy. In poor families fencing skills were transferred from father to son, and those who was richer and could afford to take lessons from professionals, often choosing expensive Fencing Masters. 1874 Early lessons father to son In 1656 the Louis XIV granted nobility to six of the most honored Fencing Masters. From that point on, Fencing Masters were able to become nobility and even to become famous. From the late 16th century to the 18th century in France, there were very few real fencing masters – for example in 17th century Paris there was only one fencing master per twenty thousand people and later in the 18th century there was only one for every thirty thousand! During six years of personal training one master was able to prepare about only five pupils, and if you think about a twenty to thirty year career, that’s not a very efficient way of teaching many fencers. That’s why in provinces across France and Europe, there were many unauthorized fencing teachers who didn’t practice officially but had much success. There was a serious need for fencing schools and academies, and the time was ripe for this to happen.

In the second half of XVII century there were more and more new fencing schools all around Europe, including France. Typical school in province was very ordinary. Often those schools were located on the first floor of the regular houses and had one a more or less large room with a dirt unfinished floor and a pair of small windows. Through these windows onlookers and passers-by liked to watch through, getting excited about exercises and bouts. Of all the furniture in such a training space was only one chair for the teacher, wooden “horse” for teaching fencing on horseback, and stand with rapiers. These schools were noticeable from the street because of the entrance sign with a hand and a rapier. But of course fencing schools in aristocratic quarters such as Saint Germain in Paris, near the Louvre and the Royal Palace were up scaled with fancy facilities, designated smoking areas and best teachers. Tuition fees for such training in the 18th century was three livres per month (1 livre = approx 8 Euro ), in addition to the entrance fee. Musketeers had an average salary of 300 livres per year. However rich people with solid income preferred to take private lessons at home. It was a common belief that a noble gentleman should hide how much effort and expense it took him to learn fencing. Private lesson costs were about from two to four livres – almost as much as a month of training in a normal school of fencing. But in private lessons, the teacher practiced noble customers not only in the usual methods of attack and defense but also a special technique – the “secret”, which guarantees victory in the battle. In addition to fencing a nobleman was obliged to be able to ride, so riding horses was part of the program. They also had a wide academic and cultural education. Students of the Academy were taught endurance and self-control, the primary weapons of the fencer. Dance and other arts were often part of these programs. Academies had to prepare nobility for the good service to the king. Between teachers and their pupils there developed relationships of noble friendship and trust. Academy teachers joined the aristocratic society and were able to find patronage for their students, while the students valued the friendship of these mentors. While there wasn’t a unified program of fencing established for these schools and academies, most schools followed the famous program of Pluvinel: fencing, horse riding, dancing, mathematics, gymnastics, and drawing. Sometimes teachers added music, history and foreign languages. Most of the morning program taught riding and afternoon – all other subjects, including fencing. The whole course was designed for two years. The most essential study taught by fencing academies and fencing masters was the study of the rules of honor, which were followed during fight and battles. After all, fencing has always been, and still is, a sport and an art for fine and noble natures – for those with honor and dignity. |

MarkoUndermaster of historical fencing ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed