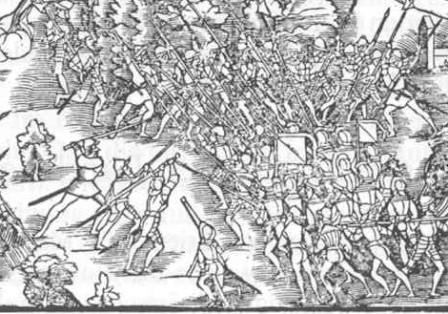

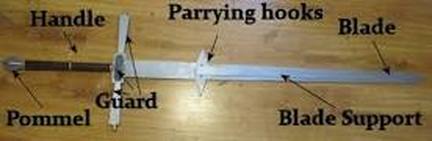

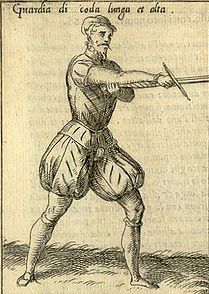

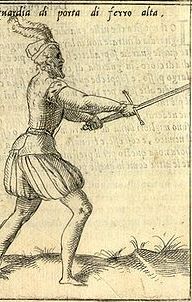

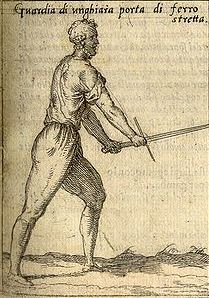

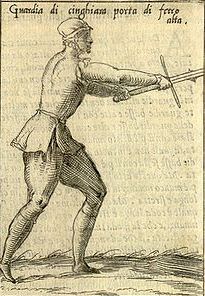

Landsckneht with zweihander The Zweihände (a non-historical modern popular term, German term for "two hander", for the more accurate Doppelhänder ("double-hander") or Beidhänder ("both-hander") is a type of large two-handed sword primarily in use during the early decades of the 16th century. The greatsword is a true two-handed sword that can trace it's develpment to the end of the 15th Century, and is typically in excess of 5 feet (150 cm). Called Greatsword or two-handed sword by the English, claymore by the Scots, zweihander by the Germans, montante by the Spanish & Portuguese and spada da due mani by the Italians. In contrast to longswords, technically, true two-handed swords (epee's a deux main) or "two-handers" were actually Renaissance, not Medieval weapons. The popular names Zweihander / Zweyhander are actually relatively modern not historical terms. It developed a fearsome reputation on the battlefields of Europe during the 16th & 17th Centuries. The Zweihänder swords develop from the bastard sword or montante ("longsword") of the Late Middle Ages and they became a hallmark weapon of the German Landsknechte from the time of Maximilian I (d. 1519) and during the Italian Wars of 1494–1559. The Goliath Fechtbuch (1510) shows an intermediate form between longsword and Zweihänder. These swords represent the final stage in the trend of increasing size that started in the 14th century. In its developed form, the Zweihänder has acquired the characteristics of a polearm rather than a sword. Consequently, it is not carried in a sheath but across the shoulder like a halberd. They are really those specialized forms of the later 1500-1600s, such as the Swiss/German Dopplehänder ("double-hander") or Bidenhänder ("both-hander") used by the german Landsknecht. Specifically, the Doppelsoldner (doublesoldier, a soldier who went to the front linesbut earnt double pay) who would use the zweihander to break pike formations and take on the task of repelling the early attackers. As an infantry weapon it was used to break up pike formations, as the honour guard defending the Unit's banner or as the preferred weapon of civilian bodyguards. The Battle of Kappel, October 11, 1531. By the second half of the 16th century, these swords had largely ceased to have a practical application, but they continued to see ceremonial or representative use well into the 17th century. Some ceremonial zweihänder, called "bearing-swords" or "parade-swords" (Paradeschwert) were much larger and weighed about 4.5 kg. The weapon is mostly associated with either Swiss or German mercenaries known as Landsknecht, and their wielders were Doppelsöldner. However, the Swiss outlawed their use, while the Landsknechte kept using them until much later. The Black Band of German mercenaries (active during the 1510s and 1520s) included 2,000 two-handed swordsmen in a total strength of 17,000 men. Zweihänder-wielders fought with and against pike formations. Soldiers trained in the use of the sword were granted the title of Meister des langen Schwertes (lit. Master of the Long Sword) by the Marx brotherhood. These weapons were used primarily for fighting among pike-squares where they would hack paths through knocking aside poles, possibly even lobbing the ends off opposing halberds and pikes then slashing and stabbing among the ranks. 1630 Einige Figuren von Fus-Thurnieren (2º MS Math.7) Frisian hero Pier Gerlofs Donia is reputed to have wielded a Zweihänder with such skill, strength and efficiency that he managed to behead several people with it in a single blow. The Zweihänder ascribed to him is, as of 2008, on display in the Fries Museum. It has a length of 213 cm and a weight of about 6.6 kg. Pier Gerlofs Donia (ca. 1480–1520) was a Frisian rebel leader and pirate. He is best known by his West Frisian nickname Grutte Pier ("Big Pier"; in the pre-1980 West Frisian spelling written as Greate Pier), or by the Dutch translation Grote Pier which referred to his legendary size and strength. His life is mostly shrouded in legend. Based upon a description now attributed to Pier's contemporary Petrus Thaborita, the 19th-century historian Conrad Busken Huet wrote that Grutte Pier was: A tower of a fellow as strong as an ox, of dark complexion, broad shouldered, with a long black beard and moustache. A natural rough humorist, who through unfortunate circumstances was recast into an awful brute. Out of personal revenge for the bloody injustice that befell him (in 1515) with the killing of kinsfolk and destruction of his property he became a freedom fighter of legendary standing. Etching of Grutte Pier, from 'Chronycke ofte Historische Geschiedenis van Frieslant' published in 1622 Early Zweihänders were simply larger versions of longswords. Later examples had Parierhaken ("parrying hooks") at the top of the crossguard as well as side rings on the hilt. A sword did not necessarily have both features. Some Zweihänders had wavy blades and were called Flammenschwert. These inflicted terrible cuts and wounds. A Flammenschwert. This is a two-handed sword featuring an exceptionally long blade and hilt, a wide crossguard, and a ricasso with a pair of parrying hooks When we talk about zweihander lets mention his part: knopf (pommel), heft (handle), creutz (crossguard), parierhaken (parrying hooks), klinge (blade). Parts of zweihander 16 masters and 2 manuscripts talk about zweihander. Masters which wrote about zweihander where: Francesco di Sandro Altoni, Carlo Giuseppe Colombani, Pseudo-Peter von Danzig, Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo, Domingo Luis Godinho, Giacomo di Grassi, Maarten van Heemskerck, Achille Marozzo, Mathern Fechtbuch (2º MS Math.7), Joachim Meÿer, Pablo de Paredes, Andre Paurñfeyndt, Jaime Pons de Perpiñan, Francisco Román, Henry de Sainct Didier, George Silver, , Pedro de la Torre. Manuscriptes about zweihander where: Las reglas del montante (CCPB000152417-8) and Sobre el arte de la esgrima (MS II/1579(2)). So lets go to see techniques for zwiehander. I will use master Marozzo manuscripts from 1536. “Opera Nova”. Let’s see what master Marozzo say in BOOK 3 which deals with the art of two handed sword. Capitula 161

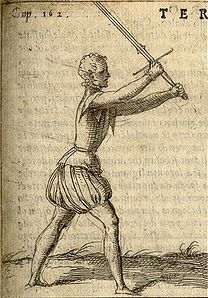

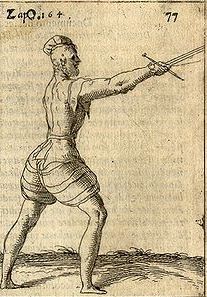

2. Remaining in the porta di ferro alta there is a need that you always watch at wide play the forward half of the sword and in narrow play you will watch the left hand for reason of the prese (wrestling). 3. You know that in the second part you remained in the porta di ferro larga. I want you to strike with the false of your sword strongly your enemy's toward your right side setting your left foot close by the right. I want you to wait for your enemy. 4. When you have made said falso you will give a mandritto tondo to the legs stepping strongly with the right foot forward. That mandritto should return to a guardia di facia throwing at such time the right foot close by the left. 5. You will raise the sword point to the face of the enemy and in this manner if he attacks your head feign a parry with your sword and abandon it, void, and in one time you will loose a roverso fendente stepping with your left foot opposite his right side. In this manner your sword will go into the coda longa e alta. 6. Do not stop. For your defense you will throw your left leg close by the right and go into a guardia di croce and in one time you will throw the right foot two hands widths behind the left and throw a rising falso dritto to your enemy’s hands. 7. In this your left foot will go behind the right and in this manner your sword will go into the porta di ferro alta, to the right as aforementioned 8. Still being in the porta di ferro alta and if your enemy is in the same guard, I want you to throw a tramazoncello with the left leg stepping towards the right side of the enemy. In this manner your sword will go into the cinghiara porta di ferro stretta and then you will thrust (in falsata) to the outside that goes to the left temple over his sword. 9. In fear of the thrust he will uncover the area below and you will give amandritto tondo to his legs going into the guardia di intrare in largo passo. 10. Rising and striking with a roverso sgualembrato to his right temple. In this you will step strongly forward towards his right side and your sword will go into the coda lunga e distessa. 11. If you remain in the said porta di ferro alta, here you will find your enemy with a rising falso manco that strikes his sword strongly. In this strike you will bring your left foot close by the right and then move the right strongly forward. You will throw two mandritti tondi: one to the head and the other to the leg. You will then re-enter the gaurdia di intrare non in largo passo. 12. Now go and watch between consideration and circling in the guardia de intrare in largo passo. For here finding your enemy in the porta di ferro alta or porta di ferro stretta you will thrust crossing above the hand. 13. For your defense you will make a “fugi e cruove” in the manner that your sword goes into a cinghiara porta di ferro alta.

6 Comments

Trent Rogers

5/5/2019 04:21:28 am

This was immensely helpful. I thought I would be searching for hours to find all the information I wanted, but here it all is in one well written, to the point article. You could wrap this in a bow and give it to any aspiring European martial arts enthusiast as a birthday gift and they'd double over with excitement

Reply

Gregory

8/29/2019 05:14:58 am

If you are talking about historical Zweihänder, then why would you use picture of a fantasy one to show its parts?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

MarkoUndermaster of historical fencing ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed